Restoration of Panchito: Civilian History of B-25J serial no. 44-30734

Civilian History: "Big Bertha"

During the early 1960’s, the B-25J was highly modified into a tanker to fight forest fires. In 1968, the B-25J was sold to the Howe brothers in Florida. It is here where the brothers modified the tanker by adding spray bars attached to the wing hard-points. The B-25J operated off of the brothers grass airfield using it as an orange grove sprayer and mosquito bomber well into the 1970’s. The B-25J finally received a name; “Big Bertha”. Imagine the sight of a B-25 screaming along at take-off power, ten feet above an orange grove, leaving a cloud of mist behind. The noise and sight of a B-25 coming at a mosquito was enough to scare it to death.

By 1978, “Big Bertha” was getting very weary and corrosion from the chemicals was taking its toll. Richard and Bob Howe had begun to use C-47s and Beech 18s for their spraying business. The brothers donated their beloved “Big Bertha” to the S.S.T. (Super Sonic Transport) Museum in St. Cloud Florida. To get “Big Bertha” to the museum, the brothers had the Florida State Police block off a part of US-192 highway so they could land “Big Bertha” on the road. While taxiing to the museum, one engine in the weak old bird seized. It had to be towed the last few feet to its new home. This once magnificent, powerful, fire-breathing beast was now a leaky, corroded, crippled derelict. Shortly after the arrival of “Big Bertha”, the museum went defunct and liquidated its assets.

A New Life for B-25J serial no. 44-30734 "Panchito"

A highly respected and talented warbird restorer, Tom Reilly, acquired the airframe and moved it to his storage facility in Orlando, Florida. Tom began a total rebuild back to its original “J” model configuration, completing the B-25J in 1986 for the new Texas owners. After arriving in Texas, the B-25J received the nose art and markings as “Panchito” from the 396th Bomb Squadron, 41st Bomb Group, 7th Air Force.

In the early 1990’s, Rick Korf bought “Panchito” and operated it from the National Warplane Museum in Geneseo, New York. Rick moved “Panchito” to the Valiant Air Command in Titusville, Florida in the late 1990s.

A New Owner for "Panchito" - by Larry Kelley

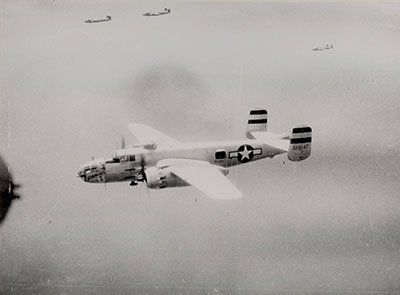

In July 1992, I was standing in the Oshkosh Warbird parking area near my UC-78, watching a line of B-25’s coming in to land after flying a tribute to the 50th anniversary of the Doolittle Raid. I clearly remember standing there, thinking, “What a magnificent airplane”. I never imagined that five years later I would own one of the planes I was watching; “Panchito”. By 1997, I found myself in the position of being able to buy another warbird. I had been flying my UC-78 for seven years and loved it dearly. I wanted something more powerful and my love for the B-25 directed me to call Tom Reilly. I asked Tom if he knew of a good B-25 for sale. Immediately, he responded that Panchito, his favorite restoration, was listed with a broker in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. I asked him to make an inquiry. By that weekend I was the new owner of “Panchito”. I will always remember standing there with Tom and asking him…….”How do you get in it?” I had a lot to learn!

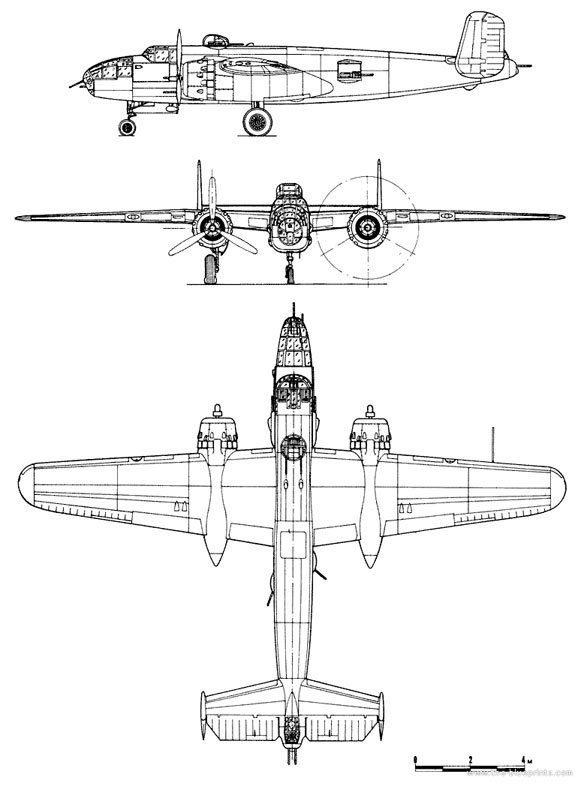

Learning to fly the B-25 was easier that I thought. Tom Reilly had trained many pilots to fly the B-25 as well as the B-17, B-24, C-47 and many other warbirds. Ironically, I found myself following the same training route of many bomber pilots of World War II. During WWII, aviation cadets first flew the PT-17, PT-19, PT-22, PT-23, etc. Basic training was next with planes like the BT-15 and BT-13. Advanced training was next with fighter pilots going into the AT-6 with bomber and transport pilots training in the AT-17 (aka: UC-78 Bamboo Bomber), AT-9, or AT-10. After receiving their wings when the cadets graduate from advanced training, they would be assigned to units for transitioning into their warplanes. Here I was, following the same course. I had begun flying in the PT-17 and PT-26 as well as the Cessna 150 and 182. I had restored my UC-78 and had been flying it for seven years. I had also flown a friend’s BT-13 and was now transitioning into the B-25J.

The first thing Tom told me was that anyone could fly a B-25. It is and easy, straightforward plane to fly. The trick was getting it to the end of the runway. At first, I did not understand what he meant. How hard could it be? Bill Dodds and Jeff Ethell (aviation author) called it the “Baghdad Dance”. Don Seiler, combat pilot of the original “Panchito, called it the “Conga”. I thought that B-25 free castering nose wheel had a demon in it! Don Seiler best described this experience in a 1979 article he wrote in Wings magazine.

“The initial stumbling-block, surprisingly, was taxiing! Learning to taxi a Mitchell was a task that caused fledgling pilots undisguised anguish, bordering on near apoplexy, and required monumental patience on the part of an instructor until his charges developed “feel” for the braking power unleashed by the press of a pedal. The main wheels are equipped with dual multiple disc brakes – 28 pair of Steel and Bronze stators and rotors in EACH wheel-that would, I believe, have been sufficient to stop a speeding locomotive on the proverbial dime. But those discs heated up FAST with excessive applications of the brakes, to a degree that made it possible to warp or even fuse metal, thus bringing much gnashing of teeth among maintenance personnel who had to change them. Use of the brakes was further complicated by the free-castering of the nose wheel. At slow speed – leaving or entering a parking ramp in close proximity of other aircraft, for example – the nose wheel had a disconcerting tendency to kick quickly, first one way and then the other, as uncoordinated applications of the pedals alternately released hydraulic pressure to the brakes. This resulted in what was commonly referred to as a “conga” with the plane in the hands of a suddenly panic-stricken novice pilot – a humorous and not unusual sight at transition school."

The other thing that immediately caught my attention was the noise level on the flight deck during flight, especially on take-off. Imagine you have a metal bucket over your head with two jackhammers attacking each side of that bucket. That is what it sounds like in the B-25! Now I know why most of the men who flew these airplanes wear hearing aids.

We base “Panchito” and the UC-78 at the Delaware Coastal Airport, Georgetown, Delaware (KGED). We can only keep these old warbirds flying with the help of volunteers who share our passion. The skill and dedication of volunteers like Josh Kelley, Paul Nuwer, Jerry Jeffers, Lorie Thomsen, Harry Fox, Mark Buck, John “Murph” Murphy, Joe Broker, Dante and Chris Volpe, Chris Burton and many others who make it possible for me to “Keep-em-Flying”. Just to do an oil change requires a forklift, 74 GALLONS of oil, two empty barrels and clothing you are willing to throw away when finished. A polish job on the bare metal requires four crews of, each with a buffer, quarts of metal polish and eight sixteen hour days. When you walk away at the end of a day of polishing, you look like you have been in a coal mine for a week! You forget all the pain when one old veteran takes your hand and thanks you for keeping it flying!

Meeting The Veterans

We started to take the plane around the air show circuit and began to meet the Veterans who flew them during WWII. I had been around warbirds since the early 1980’s when Jeff Ethell and I would travel together. When we flew “Panchito” to the air shows, we would meet many veterans. These one-on-one discussions with the veterans were deeply touching. Standing under the wing of the B-25, many veterans began to open up about their experiences in Corsica, Italy, North Africa, China, the Pacific Islands and Okinawa. Many had tears in their eyes as their memories were stimulated by the sight, sounds and smells of the airplane. It was in the B-25 that many a farm boy became a man. Some told of losing a good friend or crewmember. Stories of dedication to duty and mission, Love of country, and shocking losses were, to them, just doing their duty. Stories we call heroic are, to those veterans, just doing what they were asked to do. Over the years, I met and became friend with several of the Doolittle Raiders. Nolan Herndon, navigator/bombardier on #10 airplane off of the U.S.S. Hornet, best described how all the Raiders felt about their mission. They didn’t feel comfortable with being called heroes. They were just ordinary soldiers and airmen who happened to be already trained in the B-25 when the mission was planned. They were no better or worse than any other outfit. When asked to volunteer for a special, but very dangerous mission, they were too young and eager to get at the Japanese, to NOT volunteer. The greatest honor of my flying career was being asked to plan and lead the formation of twenty B-25’s at the 70th Doolittle Raiders Reunion in April of 2012 in Dayton, Ohio.

Standing under the wing of “Panchito” at the World War Two Weekend at the Mid Atlantic Air Museum in June of 1998, a soft spoken, white hared man with a briefcase walked up and politely asked to speak to the owner. I identified myself and he said he had something he wanted to show me. In the 1980’s, Monogram had manufactured a 1:48 scale model kit of the B-25J “Panchito”. The box cover had a good color painting of “Panchito” landing at an island airstrip. He removed from his briefcase the box cover from the model kit. I quickly noticed a photograph taped to the top left corner. My heart stopped! It was he, Bill Miller, as a 19 year old in Okinawa, July 1945, standing next to his plane – “Panchito”! He and his identical twin brother, Bob, had been the turret and tail gunners on the crew of B-25J, serial number 43-28147, the original “Panchito”. Here stood a living connection to the original airplane. For the next several hours, my questions flowed as he graciously told me the story of how he and his brother went through gunnery training together and, being twins, used a little known Army Air Corps regulation that parenthetically states, “twins, if in the same branch of service, and if militarily feasible, shall be assigned together-and once assigned, shall not be separated.” They were assigned together to Captain Don Seiler’s crew while at Wheeler Field in Hawaii. The following year, we stopped off in Bill Miller’s hometown, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to pick him up and take him with us as an honored guest to the World War Two Weekend at Reading , Pennsylvania. The whole town of Lancaster must have turned out! Television crews were at Lancaster and Reading airports to film his departure and arrival. The newspapers ran the headlines, “He flew the unfriendly skies”, as they described his wartime duty. Bill flew the entire trip in the turret, his old “office” in 1945.

At the end of World War II, the 41st Bomb Group, which included the original “Panchito”, had delivered their B-25’s to Clark Field in the Philippines for “final disposition”. The crews were ordered to park the planes, leave everything and walk away. After Capt. Seiler and Lt. Shea left the flight deck of “Panchito”, Bill Miller began to quickly remove the 8-day clock from the instrument panel. Seeing a Military Policeman (MP) approaching, he had to break off the fourth ear of the clock to get it out. He left the plane with the clock in his pocket. Back home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the clock, keeping perfect time, has an honored place on his mantle.

We have accumulated hundreds of signatures of B-25 combat crew on the replica 500-pound bombs in the bomb bay. Once, at an air show in Columbia, South Carolina, we were talking to a former B-25 tail gunner from the 5th Air Force. Parkinson’s disease had confined him to a wheelchair. He badly wanted to sign the bomb in memory of his many friends who died attacking Rabaul, Papua New Guinea. We ran all over the airport gathering up wheel chocks and boards to build a makeshift ramp to get him high enough to write his message and sign the bomb. He strained to hold his hand steady as his signature trailed across the bomb, nearly illegible. After about five minutes of straining, he had finally affixed his name to the bomb and a short message to his “lost” friends. He still had a tear in his eye when his son pushed his wheelchair back to the VIP tent.

I will forever remember sitting in the cockpit with Col. “Tic” Tokaz, former commander of the 340th Bomb Group, a B-25 outfit, in Italy during WWII. He silently sat in the cockpit staring out the windscreen. He developed a blank look and started turning pale. I asked if he was ok. After a moment, he replied that the memories were flooding over him like it was yesterday. A mission against German gun emplacements in Italy had cost him his co-pilot, bombardier, and waist gunner. He had to fly a crippled aircraft home with three dead crewmembers, himself wounded. His son and daughter, standing behind us said they had never heard that story. It was moving for us all. To him he was not something special; he was just doing his duty. The generation of veterans who fought World War II are truly the “Greatest Generation”.

The Legacy

Those of us who are honored to own and fly these unique aircraft are only temporary custodians of these icons of our military history. We owe it to present and future generations to wisely maintain and operate these treasures as living history monuments to those veterans who turned back tyranny over seventy years ago. To give us the freedoms we enjoy today. We must never forget the sacrifice of the American Soldier, Sailor, Airman and Marine of World War II as well as the other wars who never refused the call of their country to protect our way of life.